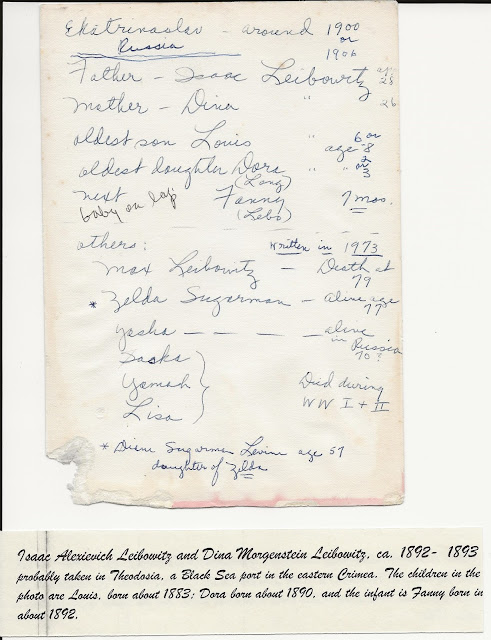

My Great-Grandparents

, Dina and Isaac Leibowitz, lived most of their lives in Ekaterinoslav ("Catherine City" referring to "Catherine the Great"), Russia. It was, and still is, a major city along the Dnieper River in the part of Russia that is in present-day Ukraine. In Communist times, it was renamed

Dnepropetrovsk (Russian: Днепропетро́вск). Following the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine gained its independence, and, in 2016, the city was renamed

Dnipro (Ukrainian: Дніпро),

|

| A Synagogue in Ekaterinoslav. |

Louis Leibowitz, my Grandfather and the first son of Dina and Isaac Leibowitz, always said he came from Russia, and never mentioned Ukraine. Indeed, according to the 1887 census, over 42% of the residents of Ekaterinoslav were ethnic Russians and only 16% were Ukrainian. In that census, Jews were counted separately and made up some 36% of the population.

As the following

table shows, the proportion of ethnic Russians and Jews vs ethnic Ukrainians has decreased considerably since the early 1900's:

A GROWING AND SUCCESSFUL JEWISH PRESENCE IN 1900 - The

JewishGen website provides good information about the history of the Jews in Ekaterinoslav. I've selected portions of text about the Jews in Ekaterinoslav from that website and interspersed some of the stories Louis told me about his time there as a youth and as a young man. I only wish I had asked him more, and that I remembered more of what he told me.

I would love it if some of my fellow descendants would contribute stories told to them by earlier relatives. If any descendants of Dina and Isaac Leibowitz in Russia, or Ukraine, or elsewhere, happen to stumble upon this website, I'd love to hear from you as well. Please post your stories as Comments to this Topic, and I may promote some to the main Topic area. advTHANKSance!

The general Russian census that took place in 1897 gives us a clear picture of the demographic and economic situation of the Ekaterinoslav Jews. There were 40,971 Jews in town, 20,864 men and 20,107 women – 37% of the general population ... one of the largest in Russia.

Of this number, 12,114 men and 3,046 women were independent providers (with 24,819 dependents): 4,531 were merchants, including 432 women, 2,969 worked in the clothing industry, helped by 4,415 dependents, 1,714 were in private service and helpers in shops, including 1091 women, 657 were occupied in woodwork and 771 in metal works. We find here a creative group, occupied not only in commerce but also in craftsmanship and light industry.

UPHOLSTERY AND KOSHER CHICKEN - Isaac Leibowitz, my Great-Grandfather, was an upholsterer. He often worked at the estates of wealthy non-Jews. Louis told me that he learned upholstery from his father and accompanied him to those estates. They did their own kosher food preparation, using ingredients provided by the estate manager.

One time, Louis was left alone at an estate and was given a chicken to slaughter. Although he had never killed a chicken, he had watched his father do so, and he knew that the kosher method prohibited chopping the chicken's head off, but required the neck to be slit, but not all the way through. So, he told me, he held the chicken and partially slit the neck. Of course, the chicken objected and burst out of his hands. It then ran around the yard, with it's head hanging down on one side. This incident, he told me, was a source of many nightmares.

This story reminds me of a poignant Chasidic Tale of how a young Jewish boy, alone in a situation similar to Louis's, was instrumental in making a rich Jewish boy's Bar Mitzvah successful. According to this Tale, a rich Jew hired several distinguished rabbis to officiate at his son's Bar Mitzvah. Each rabbi praised the wealthy Jew for his generous contributions, and discoursed on some obscure religious topic to show off their expertise.

When it came the turn of the Chasidic Rabbi, he looked around at the opulent setting and was appalled at the chutzpah of the wealthy Jew in showing off his riches. For a moment he just stood there. Then he looked upwards and raised his hands high. He said he had just received a vision of a Jewish boy from a family so poor they had to send him to work on a non-Jewish farm. This very evening, he said, the boy had turned 13 and realized he had to perform his own Bar Mitzvah! The boy knew some Hebrew prayers, but where would he find a minion of ten worshippers required to say them?

Well, the boy went to the barn and gathered a horse, a couple of cows, a few sheep, and a bunch of chickens, and he chanted the prayers. Each of the animals added their "neigh", "moo", "baa" and "cluck", and the Bar Mitzvah service was completed as well as could be expected given the circumstances.

The prayers chanted by the boy and his fellow barnyard worshipers in this unique Bar Mitzvah, said the Chassid, was so extraordinarily wonderfully that it had opened the gates of Heaven so wide that even the prayers said at this opulent Bar Mitzvah would rise and be heard.

JEWISH COMMUNITY INSTITUTIONS - Continuing from th

e JewishGen website:

A considerable number of people were involved in the dress industry, wood and metal. There were also the liberal professions: doctors, lawyers, accountants, pharmacists, employees in banks and commercial associations. Some of the Jewish companies employed non–Jewish workers, with a considerable turnover and production.

Jews owned many of the shops, as well as houses in the central parts of the town. They also founded commercial companies with the aim to by–pass the government rules that restricted their activity in the mining industry.

The development of the Jewish crafts and commerce caused a problem of credit, and this was solved by founding a credit fund for craftsmen and small business men; its founder and manager until the day he died was the engineer Moshe Bruk. In time, this institution grew and helped its members by providing the necessary credit and saving them from exaggerated interest.

At the end of the 19th century, 12 registered synagogues were active in Ekaterinoslav, 3 Talmud Torah schools with 500 pupils, and several Chadarim with 885 pupils. In addition to that there was a Yeshiva and 16 private schools for boys and for girls.

During the first years of the 20th century, under the rule of Nicolai II, the attitude of the local authorities toward the Jews did not change much; it depended mainly on the personality of the district governor. If he was an honest man, not under the influence of the anti–Semites, it was possible to advance the community matters and develop its institutions. But if he was an anti–Semite, it was difficult to care for the many needs of the community. Luckily for the Ekaterinoslav Jews, several liberal governors were in office during that time, and it was possible to develop the existing institutions and establish additional ones. However, the anti–Semitic incitement among the Christian public did not stop, and was expressed in 1904 by the attack of hooligans on the Ekaterinoslav Jews, which was suppressed by the police. ...

The income of the community was mainly from the meat tax ... Although the Ekaterinoslav Jews were only 40% of the general population in town, their mark on the economic life was considerable, due to their energetic economic activity ... As a result, the town seemed “full of Jews.” The contact with the non–Jewish population was mainly in the area of economics, and part of the Jewish intelligentsia, merchants and industrialists would meet with their Christian colleagues at the various common Societies, institutions, charity events and other public gatherings. The Jewish influence in the local press merits mentioning as well; many of the reporters, editors and writers were Jewish and readers even more. The press discussed the Jewish problem in general and showed interest in the affairs of the Community and its institutions.

The war with Japan did not affect the Ekaterinoslav Jews specifically, except for the young men recruited to the army and sent to the front.

My Grandfather Louis Leibowitz told me he was in the Russian Army, but only briefly. The Jewish community was required to meet a quota, and one of the young men who was ahead of Louis on the list ran away, so Louis was sent. Fortunately, they caught the draft-dodger and Louis was released from the army!

DISRUPTION AND POGROMS - The Russian word pogrom (погро́м, pronounced [pɐˈgrom]) is derived from the common prefix po- and the verb gromit' (громи́ть, pronounced [grɐˈmʲitʲ]) meaning "to destroy, to wreak havoc, to demolish violently". Its literal translation is "to harm". The noun pogrom, which has a relatively short history, is used in English and many other languages as a loanword, possibly borrowed from Yiddish (where the word takes the form פאָגראָם). Its widespread circulation in today's world began with the anti-Semitic excesses in the Russian Empire in 1881–1883.

Continuing from the JewishGen website:

The general revival in the country in 1905, after the [Russian] defeat in this war, included the Ekaterinoslav community. The Jews sent a telegram to the chairman of the Ministers' Council, asking to grant the Russian Jews the same rights as the rest of the population. ... The agitation among the public increased – everybody expected changes to occur; the Jewish young people, together with the others, demonstrated this quite openly.

They began discussions on the subject of self–defense, collected money and acquired arms.

Soon, however, disappointment came. On 20 July 1905, following wild incitement, rioters attacked and the Jews defended themselves. There were some wounded, but the authorities intervened immediately and the riots were stopped. ...

[However, organized riots] started on 21 October 1905. Following the “patriotic” parade through the central streets of the town, the rioters attacked Jewish homes and shops, robbed and destroyed, and murdered Jews. The defense forces ... were more–or–less ready. They organized groups armed with light arms (revolvers), who immediately began chasing the rioters from the streets. Later, however, as the army intervened and began to shoot at the members of the defense groups, they had to stop their activity, giving the rioters a free hand to continue destroying and killing, on 22 and 23 October. Only when the army received a clear order to stop the riots, the pogrom was stopped.

Louis told me about his experience with a pogrom. His family lived in a rented apartment in a building owned by a non-Jewish landlord. The building was U-shaped, surrounding a courtyard.

Their landlord, having advance notice of the coming pogrom, placed liquid refreshments for the rioters at the entrance to the building. After enjoying the refreshments, the rioters left them and their building undamaged, and went on to destroy other Jews and their properties.

Over 100 Jews were killed (the exact number is not known), over 200 were wounded. Over 300 shops were robbed, a large number of houses and apartments were destroyed, some of them burned down entirely. The censor did not allow publication of the pogrom in the press, except for a short notice – therefore many details are missing. The damage was great. The poor suffered in particular, since they remained without any means of sustenance. Few of the Christians helped the Jews; however we should mention a group of young factory workers who defended the Jews living in their neighborhood and blocked the rioters. A committee was formed, to aid the victims and donations were received from Russia and abroad, as well as from Ekaterinoslav people. ...

Out of fear, many of the Ekaterinoslav Jews left town, some immigrated to America, some made Aliya to Eretz Israel. The rioters were tried and found guilty, but were pardoned by Nicolai II…

In spite of the difficult blow, recovery took little time. The Jews invested a great deal of energy in the project of recovering their economic life. This did not happen, however, in the area of the relationship with the representatives of the authorities. Anti–Semitism was felt in the attitude toward Jews, in the various municipal and other public institutions.

Spurred by this anti-Semitism, and the prospect of a better life, Louis and four of his fellow siblings, Dora, Fanny, Max and Zelda, came to the United States in the early 1900s. They had remarkable lives here. They contributed many outstanding descendants who have also lived remarkable lives in the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

Ira Glickstein